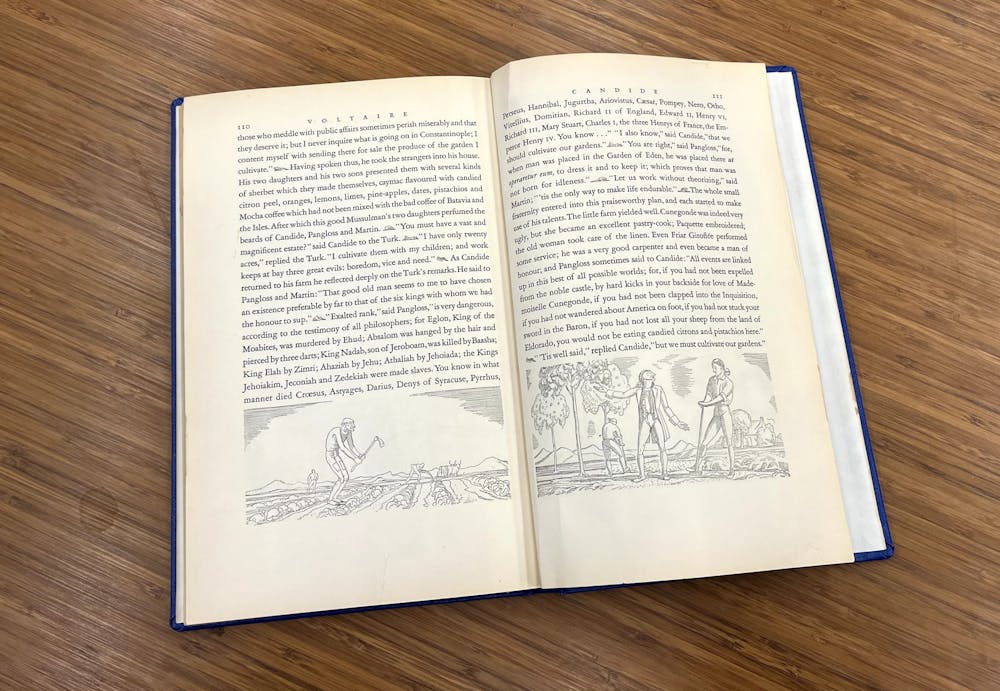

One of my favorite books that I read in high school was "Candide L'Optimisme," written by the French Enlightenment author, Voltaire.

The satirical style of the novella is rare in American literature. The casual reader must look to websites like ‘The Onion’ and ‘The Babylon Bee’, or to television shows like ‘The Colbert Report’ and ‘The Daily Show’ for modern examples. And those mostly deal with political topics.

Satire, however, is any work that pretends to take on the perspective of a particular group by using humor to exaggerate and point out its flaws or inconsistencies.

“Good satire takes the truth and blows it up to make a point and expose corruption,” said Professor Chris Lamb, Chair of the Journalism and Public Relations Department at IUPUI and former satire writer for the Huffington Post.

It often deals with themes that might seem offensive or sacrilegious to some.

Satire, however, has been a very effective tool for writers to subtly (and sometimes not so subtly) criticize anything and everything. Which is not always popular, hence why the headquarters of "Charlie Hebdo" magazine in Paris was targeted by terrorists almost a decade ago.

In "Candide," the titular character took on the perspective of a philosophical optimist, someone who dealt with the problem of “sin” by claiming that if God is good than the world we live in must be “the best of all possible worlds.”

Unsurprisingly, Candide is then confronted with all sorts of tragedies, from sickness, to disease, to the death of his friends, the burning of cities, earthquakes, and the sinking of ships. He humorously bends over backwards to justify them, eventually losing all hope. Later, he withdraws from the world and decides to “cultivate” his garden instead of theorizing or engaging in philosophical speculation. The reference to the biblical Garden of Eden is overt.

Voltaire uses this to point out the confirmation bias he found evident in that particular branch of philosophy, more often producing despair in people than an accurate understanding of the world and their place in it.

Ignoring suffering, although it was easy to do when Candide lived in a castle, would not make it go away when he experienced it himself.

Just the same, ignoring other points of view or refusing to expose students to them does not make them go away. As citizens of a democracy, they will have to come in contact with them some day. Satire, in the meantime, will help them gain a better understanding of the flaws or points of weakness in their own systems of beliefs, and as such become better prepared to defend them. Or modify their views if they find they could better live up to the values they find most important.

Satirical humor is a tool that makes more people receptive to learning, and taking a step back and critically examine their beliefs. It is the spoonful of sugar that helps the medicine go down.

Making people receptive to learning and changing their views is an essential part of reforming broken systems, according to Lamb.

“Satire can release acids that can break through the mindset that hinders reform,” he said.

The problem is, nowadays far too many people can’t even recognize satire. Large numbers of people mistake it for real news. Its ambiguity is part of the joke, but many people don’t seem to get it.

“We’ve regressed as a society to where we can no longer agree on the facts - unless something is marked satire, and what’s the fun in that?” said Lamb. “We’ve become too serious, too gullible, and too partisan.”

This comes at the same time as the so-called “fake news” epidemic. As a variation on a similar theme, fake news legitimately intends to fool people, whereas satire just tries to make a point. But both tend to use similar language and exaggeration.

“I wrote a lot of satirical columns for The Huffington Post until they quit publishing satire because the editors said it was contributing to disinformation,” said Lamb.

So why isn’t satire more of a part of our public school curriculum? That would be a better solution than simply ignoring the genre altogether.

Even more than just satire, students need a firm grounding in media literacy so they can understand how to read and critically analyze different forms of media including the news.

It would be as simple as adding a book or two to in-class reading assignments, such as Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal,” or perhaps adding a segment about internet and television adaptations of satire.

Students could then critically analyze the work and “close read” to better understand the point of view. This is an essential aspect of English education already, and adding satire to the mix would make for a more well-rounded curriculum.

Understanding the purpose and the style of the satire genre and the critical thinking skills required to point out exaggeration could be applied later in life to confront fake news.

Educators often say that the point of school is not to learn what to think, but how to think. Satire does just that. It uses humor, in an ironic and sometimes allegorical language already well-known to our youth in the form of meme culture, to encourage a critical examination of everything, including the things that we hold dear. This will not only help students better understand others’ points of view, but it will also help them better understand their own.

In the end, it will make for better students and better people.

Jacob Stewart is a junior at IUPUI majoring in neuroscience and minoring in psychology. He is the campus editor of The Campus Citizen, and editor of the Hoosier Reformer.